Crises are upon us

The availability of critical and strategic raw materials is at risk. One figure tells the situation shortly before the beginning of the Coronavirus pandemic in March 2020: the People’s Republic of China (PRC) supplied 94 percent of the global rare earth minerals and produced over 70 percent of the world’s rare earth element (REE) components and products in 2019. The European Union (EU) is almost 100 percent reliant on imports, mainly received from China.

China dominates rare earth production and processing. This imbalance creates supply chain concerns for nations dependent on these critical materials. The European Commission warns that a “nearly total” European dependence upon China for REEs, including oxides, phosphors, metals, alloys and magnets, could result in further shortages in the years ahead. Japan was recently faced with shortages. At the beginning of 2026, Beijing banned exports of dual-use items, including certain rare earth minerals, to Japan’s industrial base and began broadly restricting rare earth shipments to Japan. As a consequence, the fourth largest economy has launched the world’s first test to extract rare earth minerals from deep-sea mud, aiming to reduce its reliance on Chinese supplies amid rising geopolitical and trade tensions.

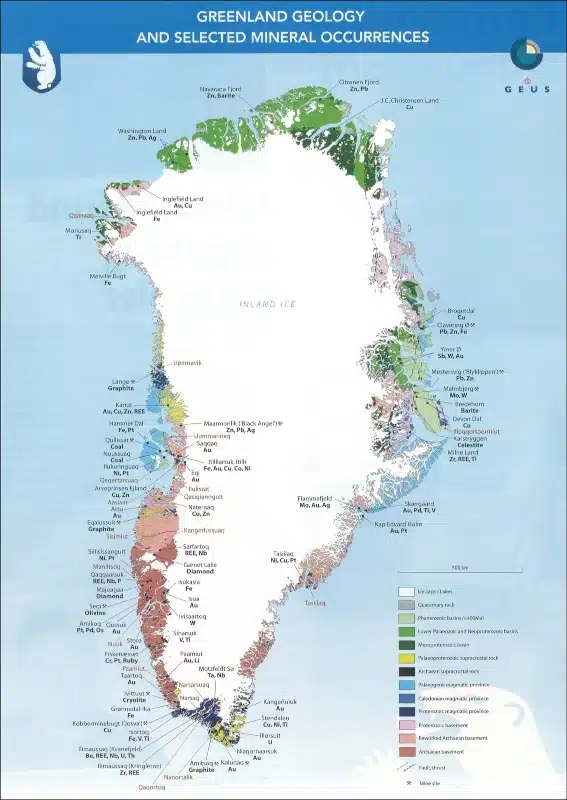

Map: Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland

The lack of access to domestic resources is a major obstacle. A likely example is Greenland, which as an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark (since 1721) owns one the largest undeveloped REE resources worldwide. The lack of key infrastructure and difficult geology have so far prevented anyone from developing commercially viable mineral resources, including Kvanefjeld (Ilímaussaq) in southern Greenland. The largest shareholder in the project is the Chinese rare earth company Shenghe Resources. This explains the fact that the PRC became involved with Greenland’s geostrategic location and abundance of mineral deposits. China’s rapid economic growth is one reason for its exploration into Greenland.

Recently, US President Donald Trump has repeatedly raised the possibility of annexing or taking over Greenland for various reasons – one of which, according to him, is the lack of protection by European NATO countries, notably Denmark. But the principal reason for the Trump Administration to gain access to Greenland is curious: its hydrocarbon and mineral resources. A complete purchase of Greenland or even a military intervention is being considered. France, Germany and other European NATO countries have rejected this. Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen warned of the “end of NATO” if “US President Donald Trump invades Greenland.”

The commercial use – exploitation – of mineral resources identified across the Arctic island will be critical to the American economy and national defence in the 2020s and beyond. The need for primary materials from own sources, such as ores and concentrates, and also for processed and refined materials is crucial for the American defence industrial sector. REEs may play the biggest role here.

Deciphering the forgotten dilemma

Again, the PRC is the largest supplier of REEs. Until at least the early 2030s, the Chinese could likely challenge the United States and the EU to demonstrate their inability to motivate industry to invest in new mining projects, thus creating additional production capacities through the respective national raw materials strategies. This situation is not new. Marcilynn Burke, deputy director, Bureau of Land Management, Department of the Interior, noted in a hearing before Congress in 2013: “Though REEs are currently of most concern to many, including the Department of Defense, it should be noted that in 2010 the United States was 100 percent dependent on foreign suppliers for 18 mineral commodities and more than 50 percent dependent on foreign sources for 43 mineral commodities,” most of which are REEs.

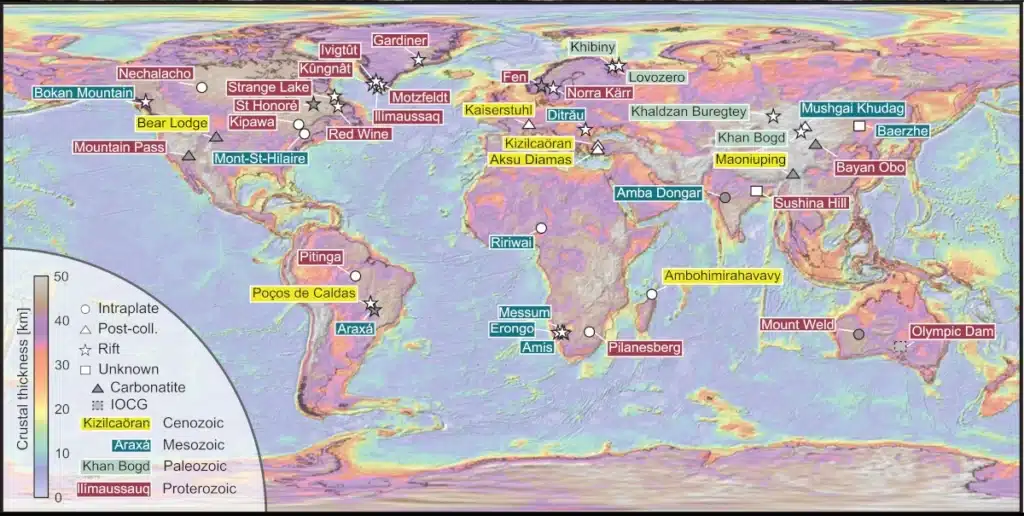

At that time, the Pentagon (now renamed Department of War) had warned of increasing US demands for imports of critical rare commodities from China, which since the beginning of the last decade has developed into one of the most important suppliers of REEs and titanium precursors for the American defence industry. Although the consumption of REEs in the US (and EU) had fallen significantly since mid-2013, members of Congress in Washington had expressed their concern that the US could become “totally dependent” on China due to a lack of own production capacities. This situation was also seen to be responsible for the closure of a number of mining and processing operations, namely in the US (MP Materials Corporation’s Mountain Pass mine in California) and Australia (Lynas Corporation’s Mount Weld mine in Western Australia), both of which were re-opened in recent years. In the US, China’s export restrictions on REEs were seen as the trigger for the “rare earth crisis” that developed over several years. The steadily decreasing demand for REEs since about 2014 (because of stockpiled materials and increased substitution, e.g., of dysprosium) did not result in further shortages, however.

There are worrying reports which provide evidence that the PRC is using its strategic endowments to constrain global supply of selected REEs and other critical commodities. Beijing could use these resources to “monopolise” the manufacturing of advanced and efficient clean energy technologies. Since a couple of years, the PRC is consolidating its rare earth production industry to such an extent that a single state-owned company (Baotou Iron and Steel Group) will have a monopoly on REE production in China’s main rare earth producing region – the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

Conclusion

The unique properties of REEs make them useful in a wide variety of applications, such as alloys, batteries, catalysts, magnets, phosphors and polishing compounds. Securing access to stable supply chains have become a major challenge for national and regional economies with limited indigenous natural resources. Access to domestic resources will be of critical importance in the 2020s and 2030s to improve resilience towards supply shortages in strategic and critical raw materials. Among other regions in the world, Greenland owns growing strategic importance. Its diverse and abundant mineral resources have caught the attention of major global powers, notably the US and China. But there is also major interest by the EU, which identified Greenland as a potential supplier of critical raw materials, including REEs. In September 2020, the European Commission has considered 30 commodities as critical raw materials, three more than in 2017. The list includes some members of the group of REEs, which are in imminent danger due to the fact that the EU is almost 100 percent import dependent on six of the 14 light and heavy REEs. Despite new finds of REE in Greenland and the Fennoscandian Shield (Sweden), the EU’s dependence on foreign supplies continues to represent a high risk. It needs to be reduced to a minimum to improve the EU’s resilience towards supply shortages in most of the strategic and critical raw materials. Besides methodologies for rare element recycling, improved access to own (domestic) reserves and resources remains critical to Europe’s economy – and national defence – in the 2020s and beyond.

Photo: Lockheed Martin