Analyse

Known unknowns

Strengthening the resilience of critical maritime infrastructure to new advanced threats

The protection of critical maritime infrastructures has become a top political priority since the September 2022 attacks on the Nord Stream pipelines in the Baltic Sea. Another incident – not far away from the destroyed pipelines – happened last November when a fibre-optic cable has been damaged. It was described to be the result of a sabotage act or potential hybrid warfare – all of which amid the ongoing war in Ukraine. That said, such infrastructures are the backbone of the global internet, carrying 99 percent of the world’s intercontinental data traffic. NATO has warned for years about the security risks affecting such infrastructures in the Baltic Sea, however. But the threat also affects critical infrastructures on land, in harbours and along coastlines. New detection and tracking systems could represent a viable tool to identify and reduce critical infrastructure vulnerabilities, to predict consequences of events and to prioritise the approbriate measures. Consequently, sensors remain the key enablers for real-time monitoring and control. Companies that deliver sensors optimised for critical infrastructure protection will create new revenue streams, as modern threats and risks are steadily growing in both frequency and intensity. It is time to overhaul the current threat analysis, since legacy technologies – analogue cameras – do not exist anymore. Time has changed much.

As widely emphasised by security experts, any of the agencies and organisations involved with protecting critical infrastructures and assets should further intensify their networking. This may include the gathering (by excellent sensors), analysis and interpretation of security-related information that must be shared between them and other sector entities. As best exemplified by more recent developments in the field of diver detection sonar technology, this will be one element of a much-needed coordination at a local level to fight endemic terrorist and illegal activities especially in the maritime security environment.

Matching the threat, that’s the answer

Among the most advanced threats, there are small unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) or drones. Besides Rocket, Artillery and Mortar (RAM) projectiles, drones can represent a serious security threat. Drones are available in any shop; but, their autonomy is rather small. Mini-UAVs can fly for 24 hours or less, and in terms of intelligence they can gather much more than what a micro-UAV can do, said industry. Therefore, critical infrastructures must be protected against the use of those systems. One solution can be found in Saab’s GIRAFFE 4A radar that was used for detecting and tracking very small drones during a number of live customer trials since about 2013. In the lab, the 4A radar showed twice the range of the company’s GIRAFFE AMB radar, Saab Group, explained.

And there are cyberattacks. Large governmental agencies and corporations anywhere in the world are struggling against an onslaught of cyberattacks by thieves, hostile states and hackers, creating extra challenges for cybercrime intelligence activities. As a consequence, these developments may have triggered new requirements for cyber intelligence, including cyber counter-intelligence. The use of Cyber Intelligence (CYBINT), like all the other specific disciplines in intelligence – HUMINT (Human Intelligence), OSINT (Open Source Intelligence), SIGINT (Signals Intelligence), GEOINT (Geospatial Intelligence) and MASINT (Measurement and Signature Intelligence) – can be the first step to understand the nature of cyberattacks, and to preserve evidence of cybercrime. However, there have been warnings that there is a general lack of information on what cyber intelligence is and how to appropriately use it. Also concerned about recent Russian cyberattacks, security organisations across Europe found that the use of intelligence, to collect, process, integrate, evaluate, analyse and interpret available information concerning foreign nations, hostile or potentially hostile forces or elements, or areas of actual or potential operations, is a vital ingredient of cyber defence.

Real-time above and underwater security

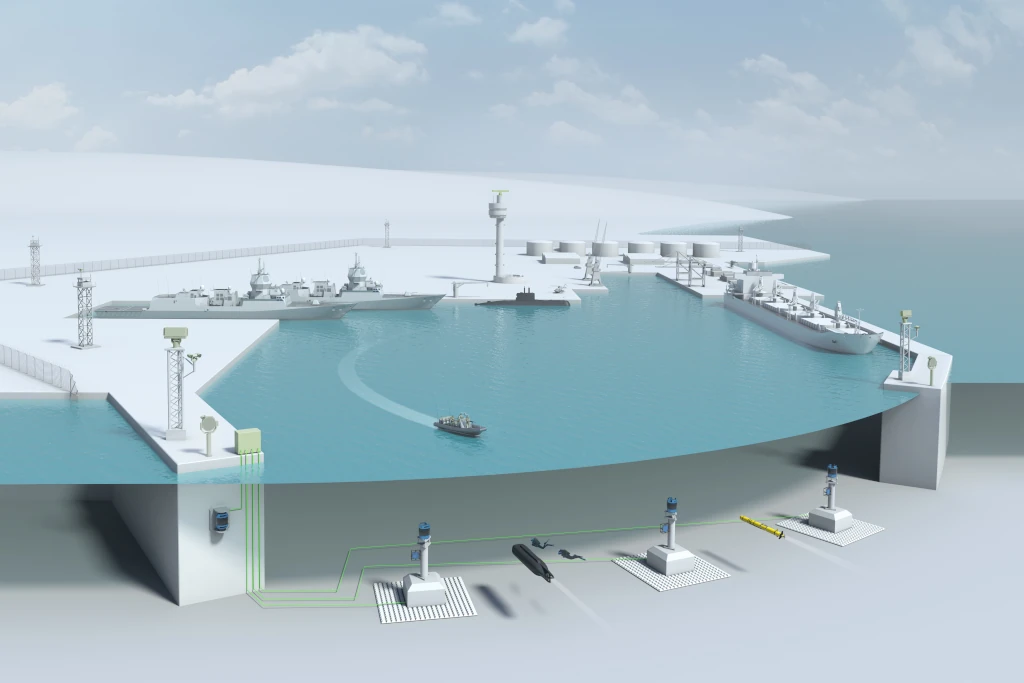

Protecting coastal installations takes new challenges. All current programmes involving modern security equipment for use in ports or harbours clearly reflect the need for improved situational awareness. Investing in more appropriate security measures (including above-the-water and underwater inspections/patrols and better training procedures), which the industry is offering, must be quickly taken into consideration to avoid costly restructuring in the future.

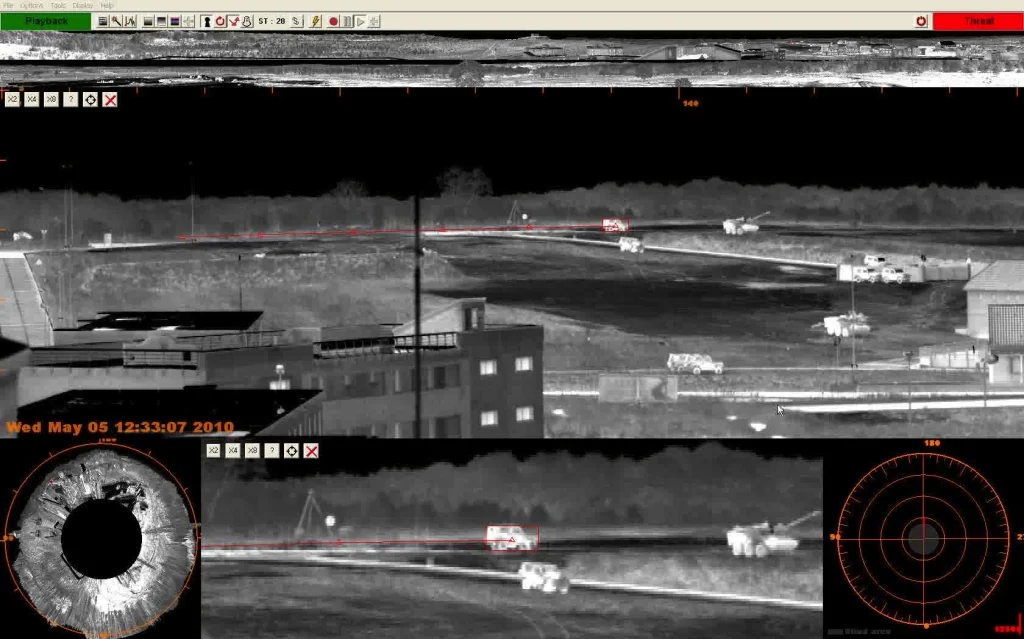

One such example known to exist since about the mid-2010s is the STYRIS® maritime coastal surveillance system currently on offer by Airbus Defence and Space. A scalable suite of sensors (cameras, radars, automatic information systems, weather sensors, radio direction finding devices), it fuses data from various sensors and generates a real-time, recognised maritime picture. As early systems used for underwater surveillance “were quite frankly not able to detect and identify an open- or closed-circuit diver [or] frogman carrying explosives in real time,” Atlas Elektronik UK (AEUK) told in 2018. AEUK was originally involved with adding significant underwater expertise to the solution. So, there have been efforts underway (since about 2010) to add an advanced diver detection sonar (DDS) – AEUK’s CERBERUS Mod 2 – to provide operators with a complete solution for the surveillance and tracking of both surface and subsurface targets. CERBERUS Mod 1 was made by Qinetiq and unveiled at UDT 2003; the underwater division was sold to AEUK in 2009 and the Mod 2 version was developed by them.

Another solution was prefixed ASCA (ATLAS Security for Coastal Areas). Developed by Atlas Elektronik in Germany for an urgent demand, it has been configured as a mobile system for expeditionary operations or as a land-based system for protecting naval bases, ports, offshore assets and coastlines. Based on the ATLAS Naval Combat System (ANCS), ASCA is described as an “effective system for coastal protection,” which, thanks to the versatile configuration possibilities with underwater and surface sensors, delivers an optimum situation picture that can be generated for any local and regional need. It is interesting to note on the sidelines that the system could be employed as the backbone for surface ships (e.g. patrol vessels) and therefore contains necessary software modules for underwater, surface or air surveillance, detection, tracking, threat evaluation and automatic alarm generation. The combat management system (CMS) software also enables quick reactions by a range of self-defence weapons to defeat asymmetric threats, including surface attacks with mortars, rockets, cars/trucks or speedboats, subsurface attacks by divers employing swimmer delivery vehicles, midget submarines or unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs), as well as suicide attacks.

Another example from Britain is the Blighter Explorer Nexus from Blighter Surveillance Systems Ltd., an electronic-scanning (e-scan) radar and sensor solution provider. It is a fully integrated, battery-operated, man-portable radar/camera surveillance system designed for rapid deployment from transport backpacks by foot patrol or from a vehicle for use in remote border surveillance, temporary camp protection, forward reconnaissance and other covert operations. Explorer Nexus can detect a crawler at 1.5km and a moving vehicle at 8 kilometres. The radar automatically cues a long-range camera to enable the operator to identify any target. A wireless backhaul link can be used to send real time sensor data feeds to a remote location for monitoring and strategic evaluation.

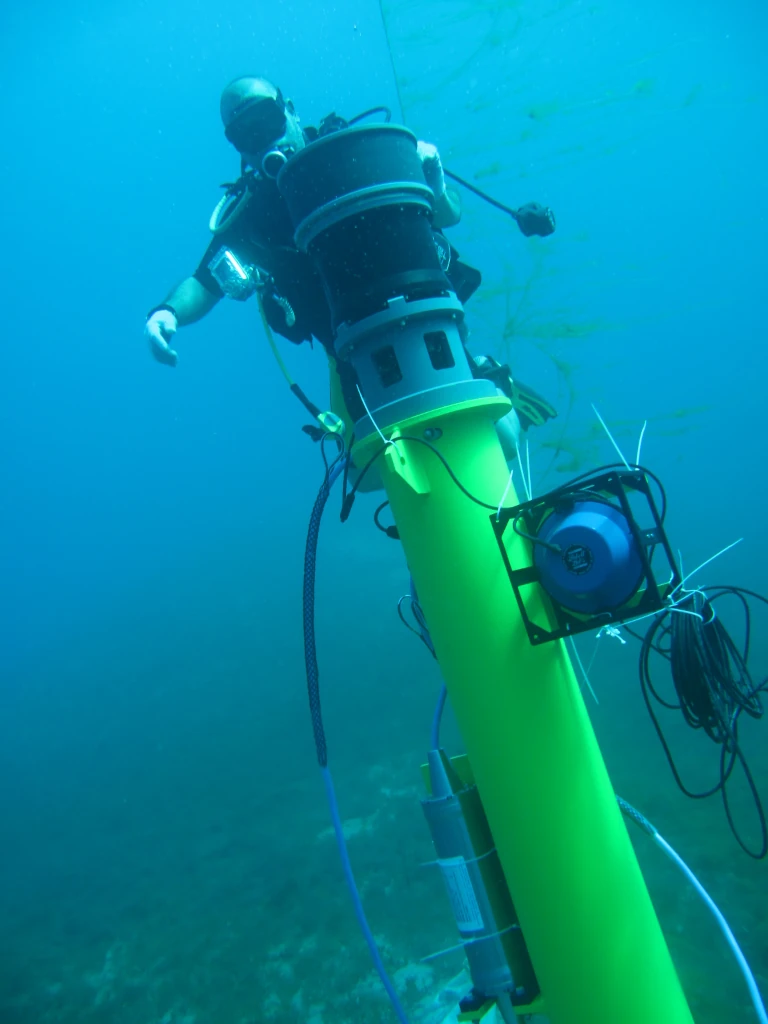

Underwater intruder detection technology – in the form of the SENTINEL Intruder Detection Sonar (IDS) – from Sonardyne International Ltd. in the UK can be used to detect unauthorised divers and subsurface vehicles approaching a critical asset from the water. According to the company, SENTINEL is the most widely deployed Commercial Off-the-Shelf (COTS) underwater intruder detection sonar technology on the market, with a proven ability to discriminate between genuine targets and non-threats, such as large fish or pleasure craft in a wide range of operational environments.

Israel’s DSIT Solutions Ltd., a subsidiary of Rafael Advanced Defense Systems Ltd., promotes its AquaShield™ underwater security system. It is an autonomous and automatic, high-performance, underwater DDS designed to provide permanent underwater security for high-value coastal and offshore assets, as well as critical infrastructure located along the coastline and offshore. AquaShield owns advanced signal processing algorithms to automatically detect, track and classify all types of underwater threats with very low false alarm rate. A couple of years ago, thesystem was chosen by London-based Energean to protect its Floating Production Storage and Offloading (FPSO) unit from underwater threats. The FPSO connects to Energean’s Karish and Tanin gas reservoirs located off the coast of Israel.

Imaging sensors, radars can do the best, says industry

There is ample opportunities for industry to address security problems. Today’s sensors can monitor environments to enable coordinated security operations. It is, therefore, little surprise that the versatility of electro-optical/infrared (EO/IR) and Ground-Based Radar (GBR) technology is continuing to prove attractive, with a large number of acquisition programmes ongoing internationally. Detector technology found in newer GBRs or EO/IR systems is suited to act as passive target detection systems able to find their targets in complete darkness and against significant background noise. Any of these measures will also include the fusion of information derived from other multiple sensors, according to Belgian EO and radar specialist Belgian Advanced Technology Systems S.A. (BATS). “These could be optical target designators, radars, laser rangefinders/designators and vehicle-mounted IR search and track (IRST) and forward-looking IR (FLIR) packages,” in combination with secure real-time data-links and decision and navigation aids. The company added: “New threats that need to be detected [in close vicinity to borders and critical infrastructures] include helicopters, small drones and other unmanned vehicles,“ including robotic vehicles on the ground. But there also is a requirement to detect and neutralise RAM projectiles and their firing positions.

There is a wide area surveillance solution available from HGH Infrared Sytems in France, which is based on SPYNEL panoramic thermal cameras and the company’s Windows-based client software, named CYCLOPE. With this solution, image processing and data analysis software enable coastal awareness with real-time 360-degree thermal videos. HGH noted in an earlier communication (2018) that they guarantee detection, tracking and identification of multiple threats including wooden boats and swimmers.

However, there is no methodology today that works well for all cases. EO/IR sensors cannot accurately enough detect targets through obscurants such like clouds, dust, rain, or fog. The use of mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) detectors allows newer devices to use micro-coolers that are not suitable for designs employing indium antimonide (InSb) technology. MCT detectors tend to function in the short-wave IR (SWIR) and long-wave IR (LWIR) bands, and achieve an improved penetration of smoke and dust. MCT detectors are capable to deliver imagery with a fourfold enhancement in resolution compared to earlier systems. They detect small-scale targets (generally smaller than 2.3×2.3m in physical size) at 4.5 times the range (8.5km) in marginal weather conditions. They also identify and recognise those targets as friendly objects or discriminate them from false targets at 2-3km or better.

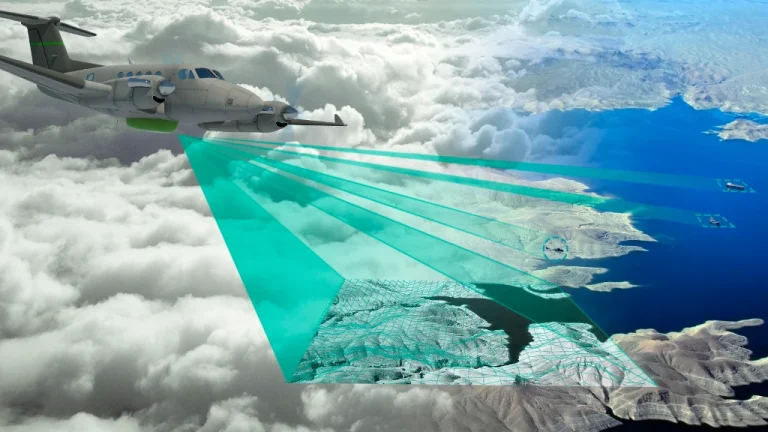

This brings us to advanced radar technology. HENSOLDT in Germany developed a multi-mission surveillance radar – named PrecISR™ – to offer synthetic aperture radar/ground moving target indicator (SAR/GMTI) capabilities, enabling operators of surveillance aircraft to detect and track, in real time, a very large diversity of small moving targets of interest (e.g., suspicious vehicles). The technology found in PrecISR ensures a reliable and accurate surveillance of static and moving threats, despite adverse weather conditions which might obstruct the EO/IR sensor results. HENSOLDT’s PrecISR airborne multi-mission surveillance radar has been recently mounted on a King Air B350 by CAE Aviation in Luxembourg. The contract was signed after PrecISR has proven impressive SAR/MTI capabilities during successful flight demonstrations. These included a joint HENSOLDT/CAE Aviation participation in the Ocean 2020 maritime surveillance exercise in Sweden. Ocean 2020 (Open Cooperation for European Maritime Awareness), funded by the European Union’s Preparatory Action on Defence Research and implemented by the European Defence Agency (EDA), was aimed primarily at demonstrating enhanced situational awareness in a maritime environment through the integration of legacy and new technologies for unmanned systems, ISTAR payloads and effectors, by covering the “observing, orienting, deciding and acting” operational tasks.

Back on the ground, Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) developed the ELM-2112FP persistent surveillance foliage penetration (FOPEN) radar, designed to detect threats that could not be identified previously in areas of dense foliage and forestry. Developed by IAI subsidiary Elta Systems, the radar has been operationally deployed for several years, protecting borderlines and critical infrastructure under adverse weather conditions and over a wide area of coverage. The ELM-2112FP assures surveillance continuity with respect to targets and threats as these enter forested areas – usually invisible for conventional motion detection radars. The radar can be connected to the same command-and-control (C2) system as other deployed radars – this capability addresses the intelligence gap that have existed up until now, due to foliage and undergrowth.

Maritime security with unmanned surface vehicles

Maritime security is a naval mission that consists of securing domestic ports, protecting main ships and maritime infrastructure against the spectrum of threats – from conventional attack to special warfare and terrorist activity. The premier pre-requisite is persistent ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance) to maintain situational awareness and target detection, as well as classification and tracking for engagement to hostile activity. This mission is quite in accordance with the deployment of Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USVs). USVs promise various naval missions without risking human life, enabling operations that require a high level of endurance and persistence – pushing people’s limits in a theoretically scaleless capacity with a comparably low cost of ownership, according to the US Department of the Navy’s “Unmanned Campaign Framework” of 2021.

In doing so, ARES Shipyard and Meteksan Defence in Turkey have launched the country’s first Armed Unmanned Surface Vessel (AUSV) programme as a result of intensive Research & Development (R&D) activities. AUSV is the first prototype platform of the ULAQ family, which for the first time successfully engaged and destroyed a surface target with guided missiles launched from an USV. ULAQ successfully completed all tests, including the 12.7mm weapon system, Selçuk Kerem Alparslan, President of Meteksan Defense Industry Inc, told our sister magazine Naval Forces in 2022.

Conclusion

Critical infrastructures of any kinds pose a unique problem for security practitioners. There is a myriad of technologies, which can be used to help secure critical infrastructures, including unmanned platforms (UAVs, UUVs, USVs), EO/IR cameras and DDS, to name just three. More sensors, in addition to analytics and new forms of ‘automating security’, are increasingly being deployed, establishing a presence in control functions. This scheme includes cheap, but sophisticated platforms to carry the sensors. For example, small unmanned aircraft or drones (e.g., the Quadrocopter Surveillor S from RKM RotorKonzept Multikoptermanufaktur in Germany) more and more have utility as surveillance platforms over areas of special interest, if there is risk of unlawful intrusion. Those systems can observe and track at best slow- and fast-moving objects like cars, speedboats, or low-flying drones – the major threats at this time.

Stefan Nitschke