European defence still is a facet of many debates today. In the face of continuing tensions with Russia over eastern Ukraine, Crimea and parts of the Baltic and Polar regions, NATO is focusing on a reinforcement of its naval capabilities and assets. Back in the early 1980s, the Soviet Union (USSR) and its western satellite states were able to deploy both powerful naval and air force contingencies at every time. In 1981, the situation in Poland was worsening. Following strikes, demonstrations and continuing food shortages, the country was plunging into economic depression. In October, the general secretary of the ruling Polish United Workers Party (PUWP), Stanislav Kania, was replaced by General Jaruzelski, the commander of the armed forces. On 13 December 1981, he declared martial law; activities of many organisations, including Solidarity, were suspended and over 5,000 activists, including Lech Walesa, were jailed. Jaruzelski indicated that the crackdown was necessary to prevent Moscow’s intervention.

The European defence policy at that time meant that European NATO member states were arguably dependent upon the link with the United States, Vice Admiral Sir Ian McGeoch, wrote in his editorial released in Naval Forces IV/1981. He insisted that the United States twice “came to the rescue” when western Europe was in thrall. Her closest, but not always strongest ally, the United Kingdom, learned over the several decades that her military might be extended in depth for her protection, since Britain was of vital importance to NATO as a main support and reinforcement base and link with North America, as suggested by Sir McGeoch. Both the United States and Britain, as well some other European allies were making great efforts to expand their naval capabilities and especially shore-based aircraft for strikes against naval targets, with Germany operating a naval air arm onshore with nearly 100 F-104G combat aircraft and a reconnaissance squadron of 30 RF-104Gs. Others, like Denmark, Norway and the Netherlands, were lacking base naval wings ashore. We are not talking about aircraft carriers here, since the French carriers at that time (1981) were old and replacements were unlikely to be in service until the end of the decade. However, Europe’s security was governed primarily by geography, meaning that the Atlantic could represent a battleground that the Soviet Navy and her allies could not cover completely all the time. The greatest menace, however, was the constantly emerging mine threat and the growing size of Soviet land-based, long-range reconnaissance and bomber aircraft, which in the course of rapidly developing technology in the field of guided missile systems, represented a tremendous problem here.

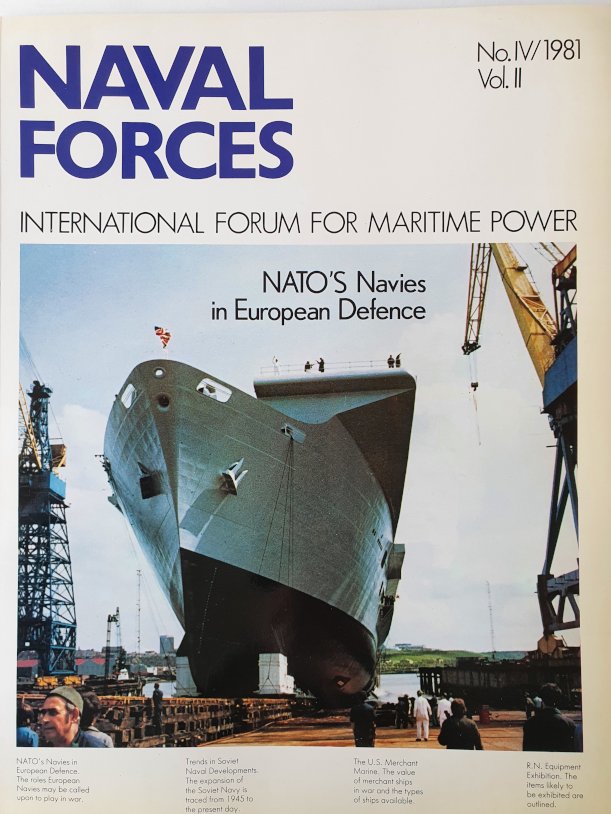

However, except for attack submarines, NATO could muster more surface ships than can the Warsaw Pact member countries – 306 vs. 248 cruisers, destroyers and frigates. Christian Eliot warned in his six-page article, entitled “NATO’s navies in European defence”, that European NATO countries would not expect their own meagre numbers to be increased to any great extend by the US Navy. Therefore, the Europeans had to plan their naval defences only on the number of assets available on their own continent. He suggested that the “traditional” frigate – long before the advent of the first ships with improved anti-submarine and air defence systems – was not the “best medium” for carrying out submarine hunting. Sure, back in the early 1980s, the frigate’s typical sonar was incapable of submarine detection at great depths. The situation today is different, since any decision made by NATO countries during the 1990s and 2000s was certainly affecting the whole alliance and might have caused European NATO partners to think twice about their present roles and their frigate building programmes.