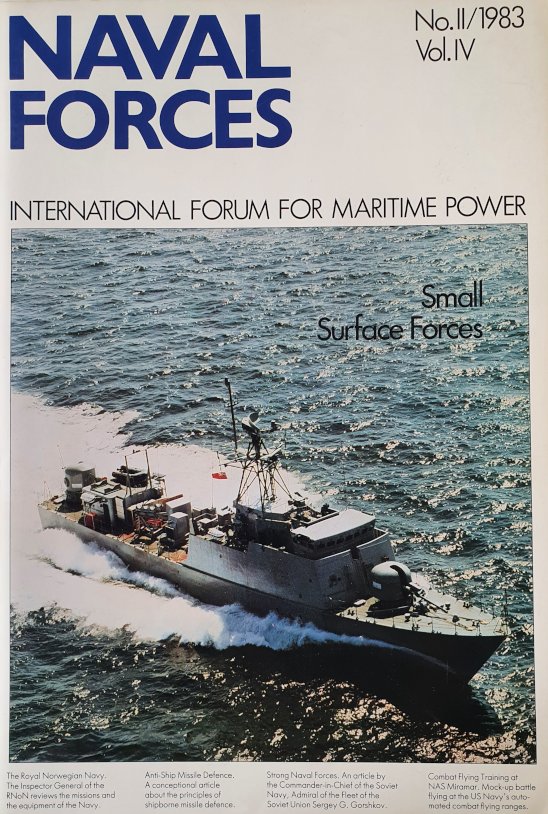

One silver lining for NATO – in the early 1980s – was Norway and its unique naval expertise. Norway, which joined NATO as a founding member in April 1949, was constantly developing its military force in support of the Alliance’s northern flank maritime posture. In the second Edition of Naval Forces in April 1983, Rear Admiral Roy Petter Breivik, the then Inspector General of the Royal Norwegian Navy, noted Norway’s border with the Soviet Union – and a unique geography with an archipelago of some 150,000 offshore islands – constituted a significant factor and challenge in all Norwegian defence planning. He added that the close proximity to the Kola base complex and the operating areas for Soviet strategic nuclear submarines in the Barents Sea would have significant impact on Norway’s and NATO’s security. A modernised navy was in fact essential for Norway to “confront an aggressor with a multi-threat,” the Admiral stated. The philosophy behind an “anti-invasion fleet” (consisting of 15 coastal submarines, 20 gun boats and 26 torpedo boats) was to build a well-balanced force consisting of as many as light, versatile and inexpensive combat units. But the author warned the navy would need to further refine and improve its fighting power. So, later improvements (1984-1988) included the incorporation of modern anti-ship missiles, thus establishing the strongest possible resistance against a seaborne invasion. In his seven-page “Strategic and Naval Policy” report, Rear Admiral Breivik also warned of decreasing numbers of coastal submarines. He explained, “a comparison between the original goal of twelve submarines and the six or at best eight submarines to be built […] reveals an alarming drop in quantity.” What characterized the 1980s so succinctly was the fact that submarines remained a “priority one task” of Norway’s defence concept. And the Admiral spoke of ‘lessons learned’: “We should be prepared to improve significantly to retain a reasonable readiness and combat effectiveness in the years to come.” In his conclusion, the author was convinced that the Royal Norwegian Navy has the inherent flexibility to adapt to the structural problems which are looming on the horizon…

In another (four-page) “Strategic and Naval Policy” report, Sir James Cable (he retired from the British Diplomatic Service as Ambassador to Finland in 1980), investigated “maritime power” as the potential capacity of a nation dependent on the sea. In his introductory note, the author noted: “Maritime power […] is the ability to employ force, on or from the sea, as an instrument of policy.” This, however, will be limited by two main factors: first is distance as the greatest handicap to exercise of naval force, which, according to the author, demands more ships and better ships. Second are constraints of time – imposing two different demands on the contestants: the ability to react quickly and the ability to sustain a protracted conflict. This all need operational concepts that are executable. So, maritime power is effective, but it is variable and relative. It can neither be measured nor compared without first answering that awkward question: “Power to do what?” In his concluding remarks, the author said that for 37 years, there has been no major war at sea and no “alliance war” – except the Falklands War in 1982 and some “little actual combat at sea” in the 1974 dispute between Turkey and Greece – where any kind of war which had to be won or lost on and from the sea. To date, we have gotten many answers to serious questions about the role of maritime power, many answers on accelerating new technologies and many answers on delivering new technology to the naval battlefront. We do know that today, the strength of maritime forces is an area of military capability in which NATO still has a technological edge.