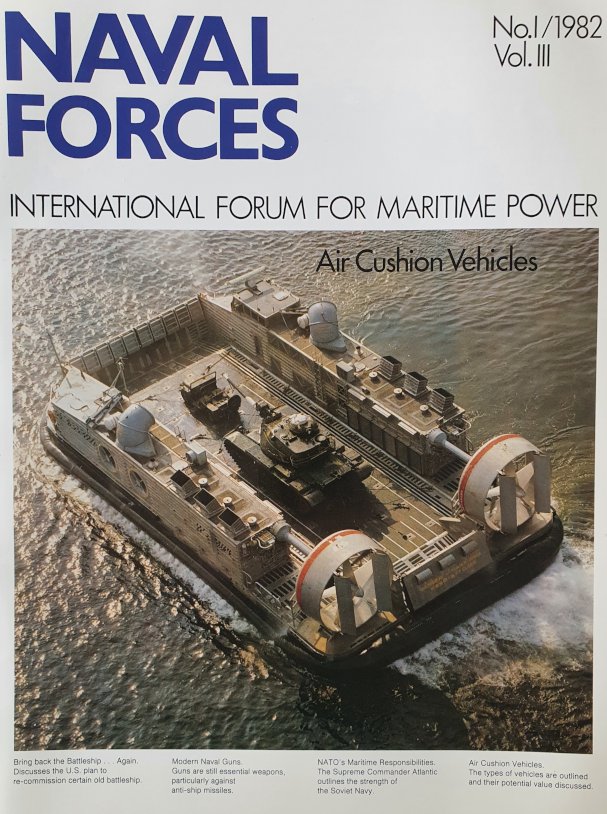

”Where others…fear to tread,” that was read in an advertisement by British Hovercraft in the first edition of Naval Forces in early 1982. It was not surprising that the British at that time had a good deal of technological expertise in the field of ACVs – air cushion vehicles – that led to exciting moments in the years to come. During the 1980s, ACVs became an option for a rather limited number of naval fleets, as naval expeditionary forces recognized the benefits they can offer. In the form of the LCAC – landing craft air cushion – first deployed by the US Navy in 1989, the idea of air cushion still remains in today’s order of battle. Forty years ago, the hovercraft’s success was that it offered naval fleets an effective transport system for high-speed service on water and land, leading to widespread developments for military vehicles, search and rescue and commercial operations. Those vehicles have been in service with a number of naval and coastguard services around the globe at that time, including Bahrain, Canada, Egypt, Finland, France, Hong Kong (now officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China), Iran, Israel, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom. David Fitzgerald, a former staff member to the US Senate Armed Forces Committee and a commander in the US Naval Reserve, wrote a lengthy report in Naval Forces I/1982, discussing the various operational and manufacturing programmes at that time. The reason for pursuing ACV development was simple: it represented a technique that allowed a sea-going craft to be completely amphibious. And today? The role of amphibious warfare grows. ACVs are suited for such operations until today. Naval Forces I/1982 found that NATO navies were accelerating their missions in their areas of responsibility, maintaining control of the vital North Atlantic sea lines of communication. That task was – since at least the mid-1970s – threatened both directly – by an enormously more capable adversary – and indirectly – by events far distant from NATO’s originally conceived area of responsibility. The author, Admiral (US Navy) Harry D. Train, II, at that time Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic NATO, explained in a three-page essay that the continuous Soviet effort to secure base rights in West Africa and other areas where Soviet air and naval forces could have comparatively free access to critical sea lines was cause for concern at NATO’s headquarters. This situation caused the alliance’s already limited forces to be spread thinly over large regions – from Newfoundland to the East of the Mediterranean Sea. Over the years, Soviet warships gained supremacy in several fields of naval armaments. Isn’t it the same situation today? The vulnerability of NATO fleets today is not only their erratic presence on the world’s oceans but also their degraded capabilities, notably in the field of long-range strike. That has led to a precipitous decline in naval power available to surge in the event of a high-end conflict. In a 2017 study, the Washington, D.C.-based Center for a New American Security (CNAS) found that Europe’s combat power at sea was about half of what it was during the height of the Cold War. “Atlantic-facing members of NATO now possess far fewer frigates – the premier class of surface vessels designated to conduct [anti-submarine warfare] ASW operations – than they did 20 years ago,” the study found. But with the US increasingly focused on Asia and amid tension between Russia and Ukraine, the European allies are becoming aware of the need to grow their naval forces and regain high-end capabilities they once had. Remember Russian President Vladimir Putin’s voicing concern that NATO could potentially use Ukrainian territory for the deployment of missiles capable of reaching Moscow in just five minutes while Russian warships armed with the latest Zircon hypersonic cruise missile would give Russia a similar capability if deployed in neutral waters. Welcome to the new era of naval warfare…