More than ever before, unmanned underwater vehicles will enable navies to achieve a continuous in-theatre presence in varying mission scenarios.

Navies around the globe intend to use them in the wake of emerging threats. Now, just 48 months after the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian War, more and more uncertainties are emerging from symmetric warfare scenarios, confronting today’s naval forces with “new old” threats that must be taken into consideration when it comes to the modernisation of naval fleets.

It is widely accepted that unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) in particular will be a key capability in the years ahead. This year’s Undersea Defence Technology (UDT) exhibition in London (14 – 16 April) will feature a highly dynamic and innovative but volatile UUV market with great growth potential that is expected to have a value of around US$8.14 billion (€6.9 billion; £6 billion) by 2032, according to a 2024-2032 market study and forecast released by Fortune Business Insights; for comparison, the India-based organisation quoted in their 2026 report that the global UUV market accounted for $3.34 billion in 2024.

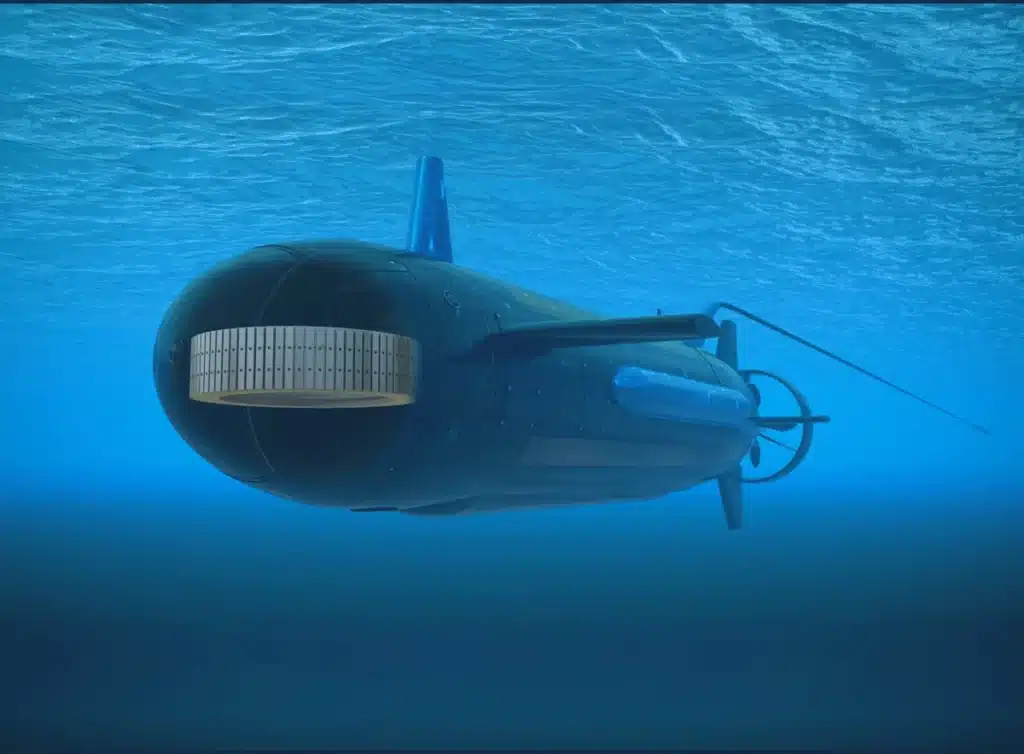

Generally speaking, not only the leading manufacturers that have a voice on a global scale, but also the multiplicity of small and medium-sized companies should play key roles and have plenty of potential growth. As an example, EUROATLAS, based in Bremen, Germany, is offering the Greyshark™ system, an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) featuring an emission-free hydrogen propulsion system that is described to set new standards for range, endurance and sustainability. According tot he manufacturer, Greyshark combines bionic design, advanced sensors and an innovative fuel cell propulsion system in one powerful platform. Equipped with intelligent sensor technology, the AUV handles ISR (intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance), MCM (mine countermeasures) and CUI (critical underwater infrastructure) completely autonomously and flexibly. Equally remarkable is its dolphin-inspired underwater communications system, based on decades of polar and avian research conducted by Dr. Rudolf Bannasch, founder and co-CEO of EvoLogics headquartered in Berlin, Germany. It enables exceptionally robust acoustic communication with other AUVs and allows genuine swarm operations, for example with other Greyshark AUVs or the small Quadroin AUV.

Today’s and tomorrow’s UUV or AUV missions cannot be successful without new technologies like artificial intelligence (AI). In doing so, the Greyshark AUV is fitted with AI-supported passive and active sensor technology that can be used (individually or in swarms) for various missions: protection of critical infrastructure; submarine reconnaissance and deterrence; and mine or unexploded ordnance detection. Delivering quite similar capability, DSIT Solutions Ltd. in Israel developed GhostFin, a new multi-mission sonar suite for UUVs. In a January press communication, the company noted that GhostFin narrows the gap between unmanned vehicles and traditional submarines. The new solution consists of an active array and two-sided flank array sonars (FAS), a passive towed array sonar (TAS) and a bow array sonar (BAS). The system’s advanced data processing capabilities enable platforms to operate in fully autonomous mode – equipped with decision support tools as well as target detection, tracking and classification functionalities.

To conclude, new technologies arising from current research and development (R&D) activities are set to play a pivotal role in maritime defence operations in the course of the present maritime security environment. Most of them are intended to shape naval fleets rapidly, but this process suffered in recent years for various reasons, including: wrong decision-making by governments and defence contractor management; shrinking defence spending in new ships and equipment; and slow increases in spendings for research, development, validation and evaluation. All of which could have effects on the variety of procurement programmes in this decade. To be sure, naval fleets in many parts of the planet were faced with severe deficiencies in materiel and personnel since about the mid-2000s, in addition to budget realities and increasingly complex procurement procedures that “rocked” the naval community in recent years.

Photo: EUROATLAS

When looking at NATO as the world’s largest defence organisation, this process goes even back to the mid-1990s. Over the past three decades, which have seen NATO’s involvement in expeditionary and peacekeeping missions, some of its key naval/maritime capabilities were substantially eroded – similarly to air power that suffered from immense reductions of capabilities. To make up for lost ground, some of the efforts currently undertaken by naval fleets might well translate into new programmes and will explain how they will act in future conflicts. How manned/unmanned collaboration will influence traditional naval warfare is a crucial question that will be answered here.

Conclusion

ROVs/AUVs and UAS (Unmanned Aircraft Systems) are now being embraced by most of the world’s naval powers. Many nations do have a vital requirement of unrestricted and immediate access to sensitive, unfiltered, and ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance) data in near real-time, for which Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs), Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USVs), and unmanned aircraft represent the ideal platforms for four principal reasons: First, they are expendable; second, they can be more survivable in high threat environments; third, they are scalable; and fourth, they are potentially more affordable in terms of lower life cycle costs. Low-cost and low-risk alternatives such as the UUV will be able to take a load off the submarine moving forward in the future operating environment.

There is an increasing need for UUVs to function as a ‘force package’ mainly in low-intensity conflicts. The need for closer cooperation between submarines and UUVs is a challenge. Deployed from submarines, UUVs can be deployed for a variety of tasks, including Rapid Environmental Assessment (REA), mine reconnaissance, and optical observations to obtain imagery of underwater objects. A covertly operating submarine can also utilise UUVs for guiding Special Forces teams to their landing zone, for which an online data-link to the submarine is required.

The use of unmanned aircraft as sensor platforms provides multiple advantages. First and foremost is the extended reach possible. An autonomous system like a small tactical drone will not be limited by a tether or other communications constraints; second, the independence of an UAV allows it to operate discretely, with a minimum of exposure of manned assets. Combined with the reach, this means that a small UAV may now penetrate previously denied or unsafe areas; and third, continuing development is leading to the ability to deploy multiple systems, which results in an extended network of sensors able to deliver critical data in a timely fashion.